Krista Svalbonas

What Remains

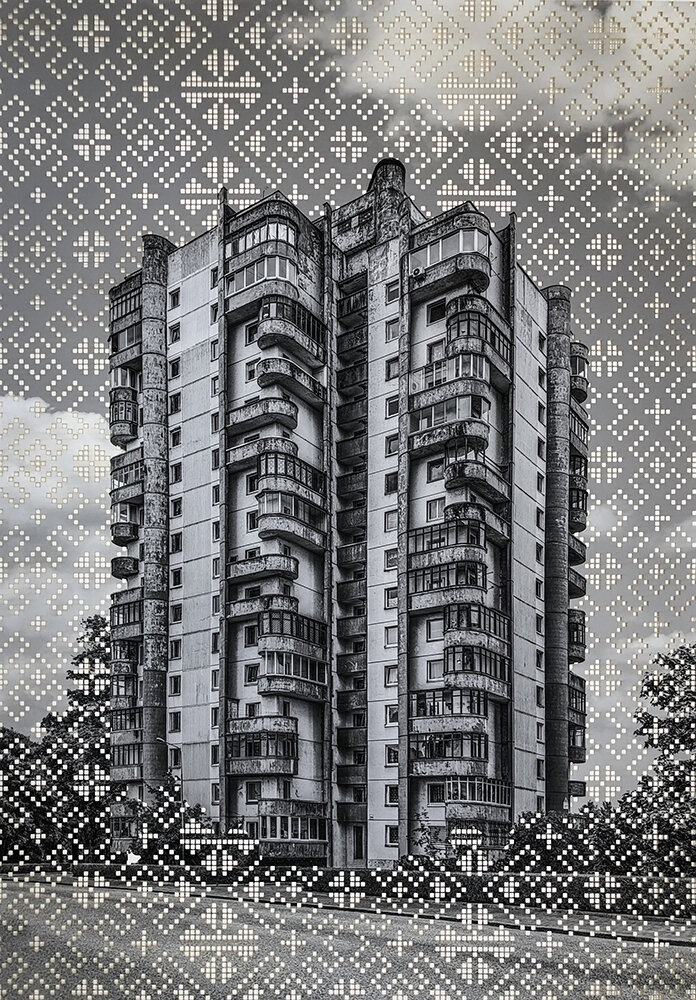

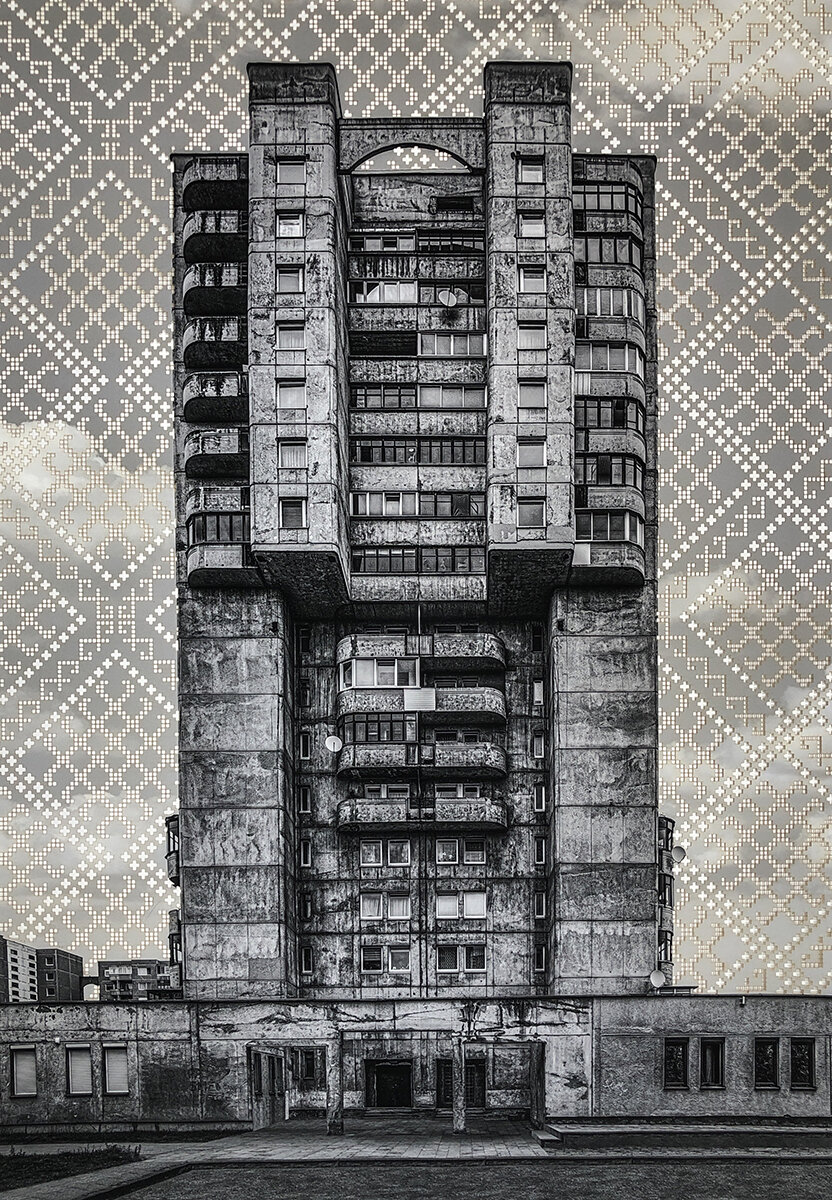

What Remains combines photographs of Soviet architecture in the Baltic region with traditional Baltic textile designs. Using a laser cutter Svalbonas cuts textile patterns directly onto her black and white photographs of these cold and imposing buildings. This series explores the power of folk art and crafts as a form of defiance against the Soviet occupiers. It does this by focusing on how traditional textile designs provide a counterpoint to Soviet-era architecture and the memory of its totalitarian agenda. The juxtaposition of concrete structures with folk art designs also references the strength and determination of the women who created the weavings. Overall, this work examines the ways in which people are shaped by their environment, and how they can rebel against it to preserve their identity and culture

Migrants

Ideas of home and dislocation have always been compelling to Svalbonas as the child of parents who arrived in the United States as refugees. Born in Latvia and Lithuania, her parents spent many years after the end of the Second World War in displaced-persons camps in Germany before they were allowed to emigrate to the United States. Her family’s displacement is part of a long history of uprooted peoples for whom the idea of “home” is contingent, in flux, without permanent definition and undermined by political agendas beyond their control. Perhaps as a result, Svalbonas is fascinated by the language of spatial relationships and by the impact of architectural form and structure on the psychology of the human environment.

Photography also plays a key role in this history of displacement: photographs were among the few possessions her family was able to take with them when they fled the Russian occupation. Photographs documented a home and a country that most Baltic refugees, including her parents, thought they would never see again. Svalbonas was raised on these visual memories, and the accompanying stories of a “homeland” that remained distant and inaccessible — until the unimaginable happened in 1991, when the Baltic states regained their freedom.

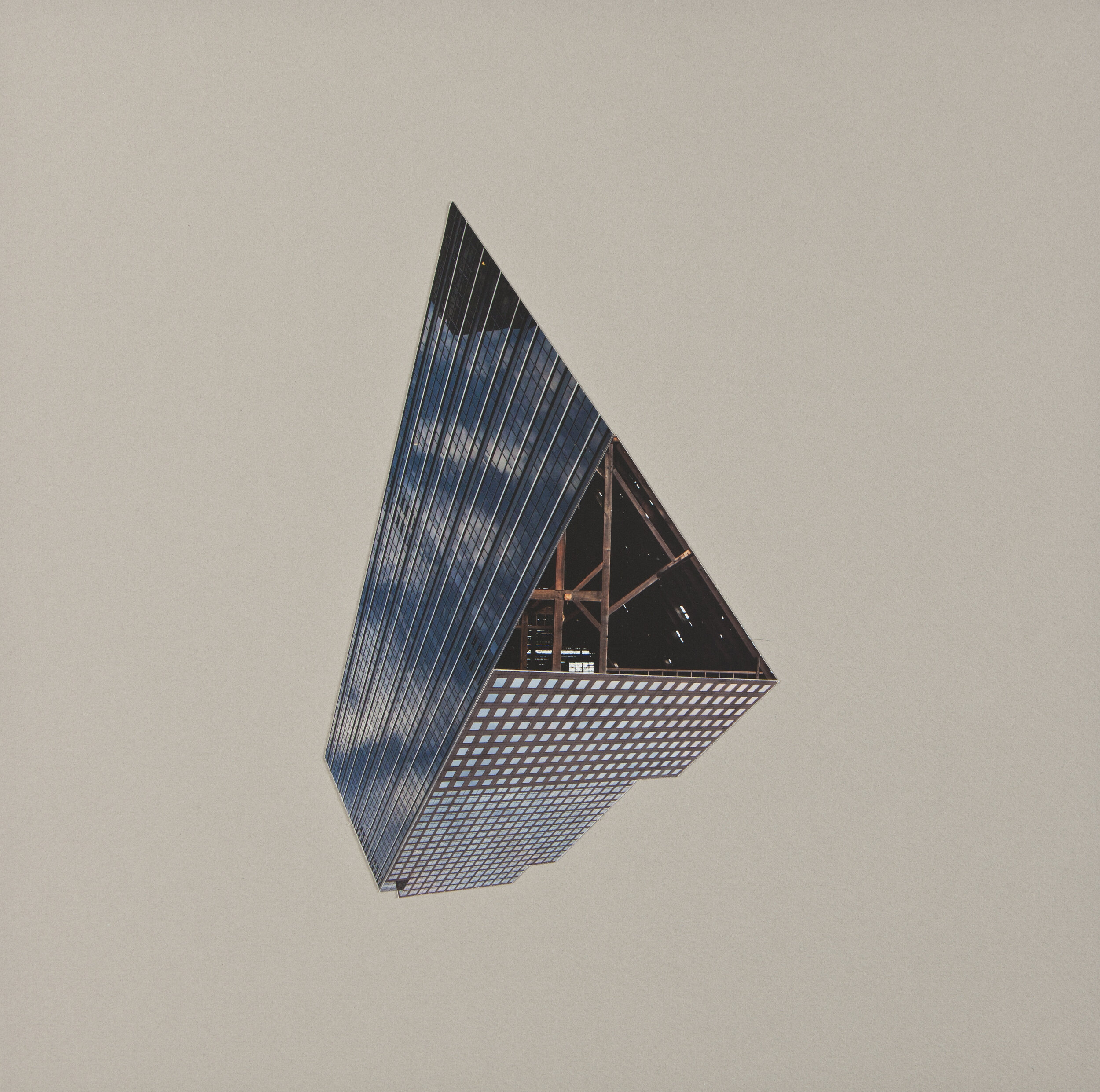

Complicated by this family history, Svalbonas’ definition of home constantly oscillates between past and present. “Migrants” began with photographs she took in the three locations she has called home in the past eight years: the New York metro area, rural Pennsylvania, and Chicago. Taken with digital camera, camera phone, and point and shoot, each image is a visual sketch of the genius loci of the landscape at a particular moment in her history. Svalbonas cuts and reassembles the images in sets of three, creating hybrid structures that reinterpret and reinvent architecture, disrupting space, light, and direction. At the same time, because the triangle is the simplest stable two-dimensional form, anchoring each piece in three geographical points creates a stability that acts as counterweight to the sense of dislocation. “Migrants” turns an analytical gaze on the architecture of her past and present while offering a personal reflection on the nature of home.

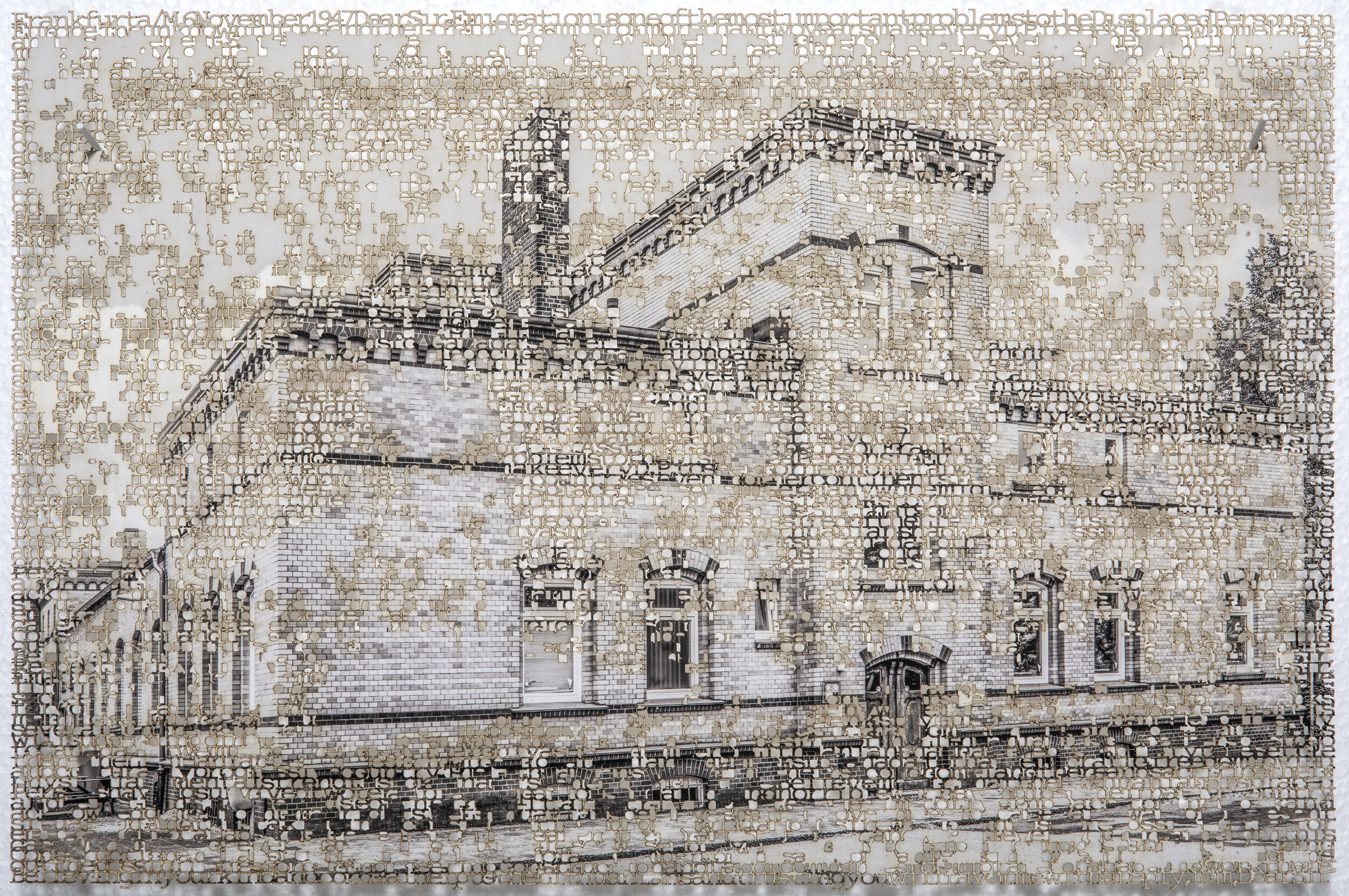

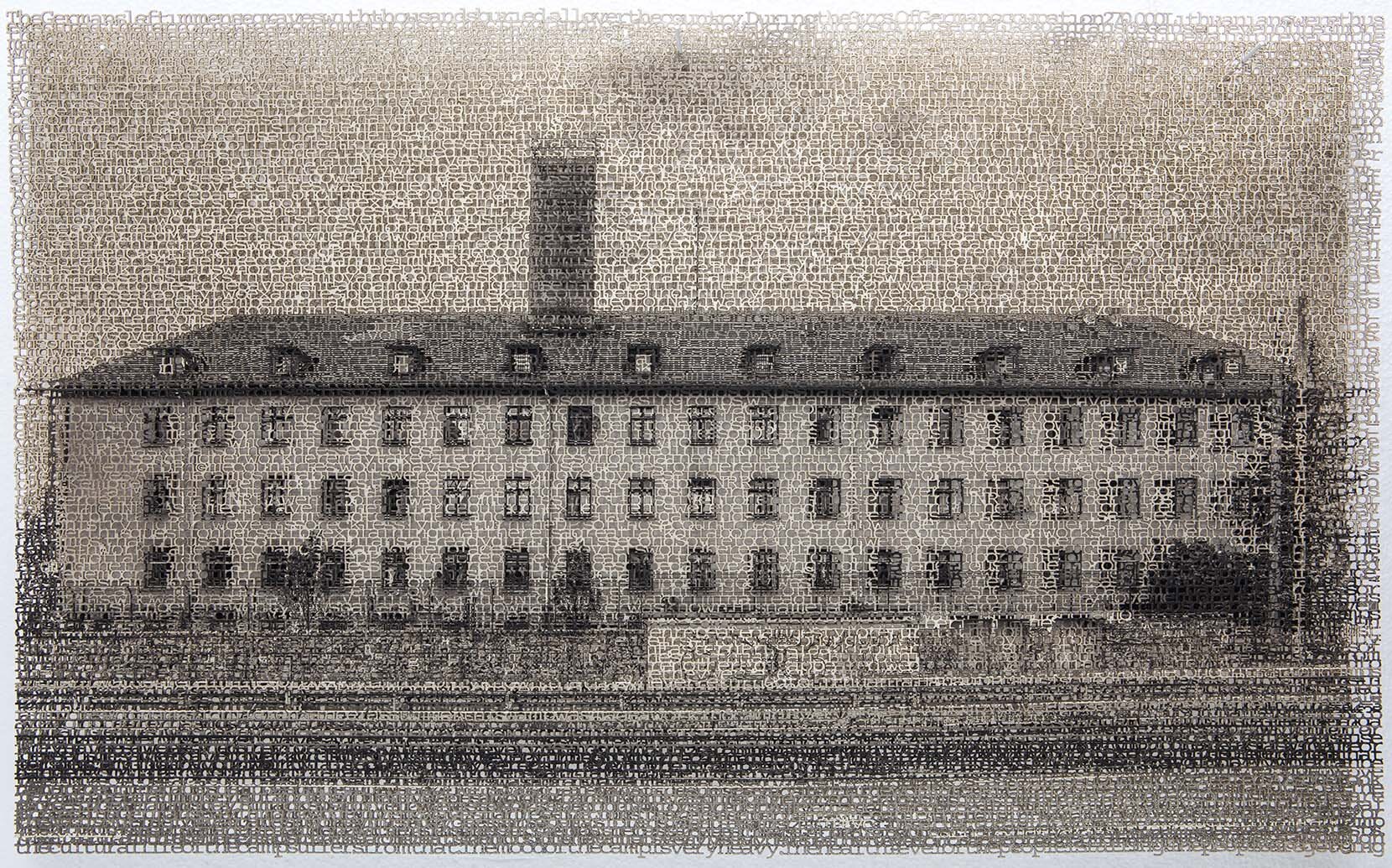

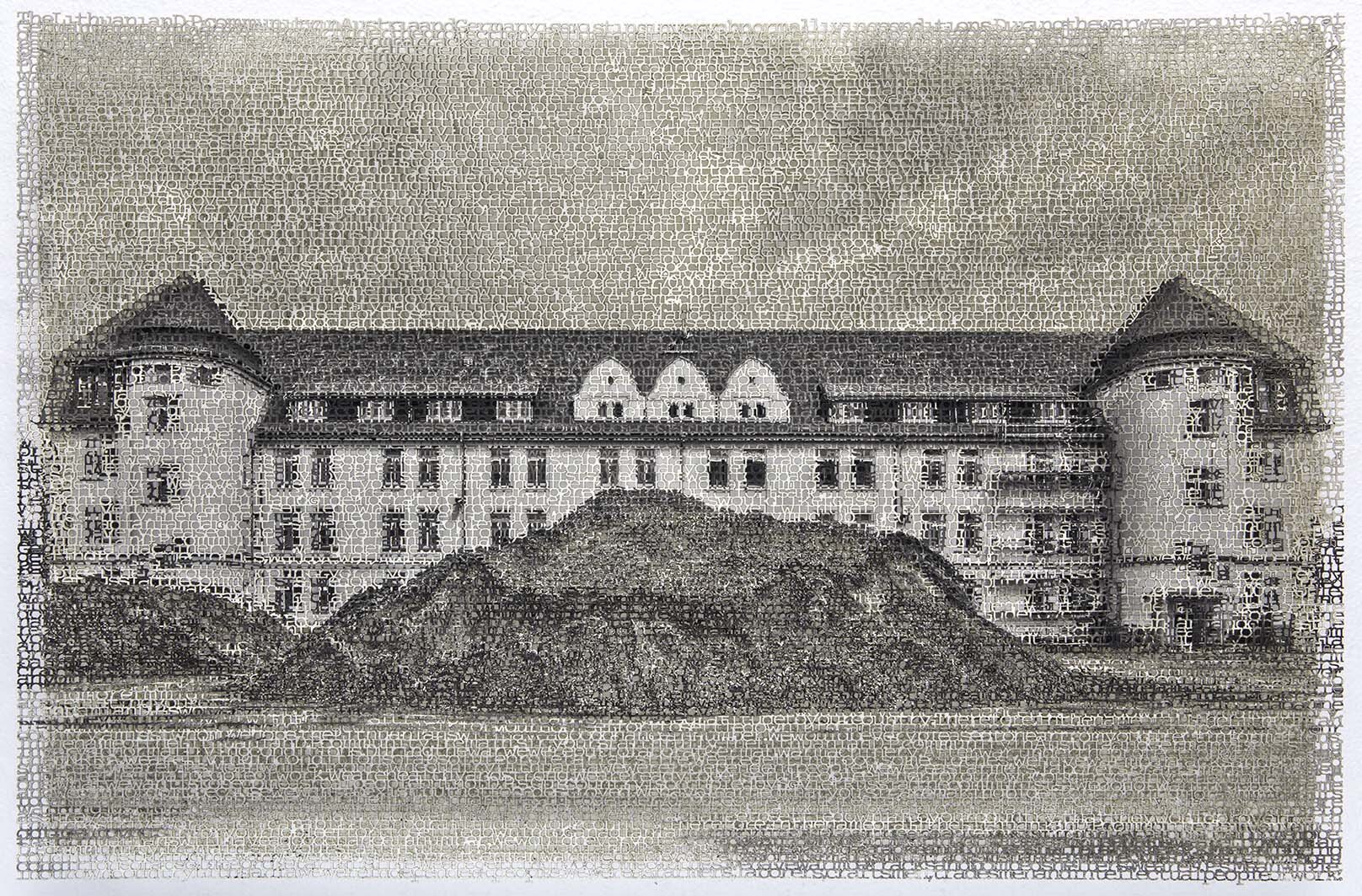

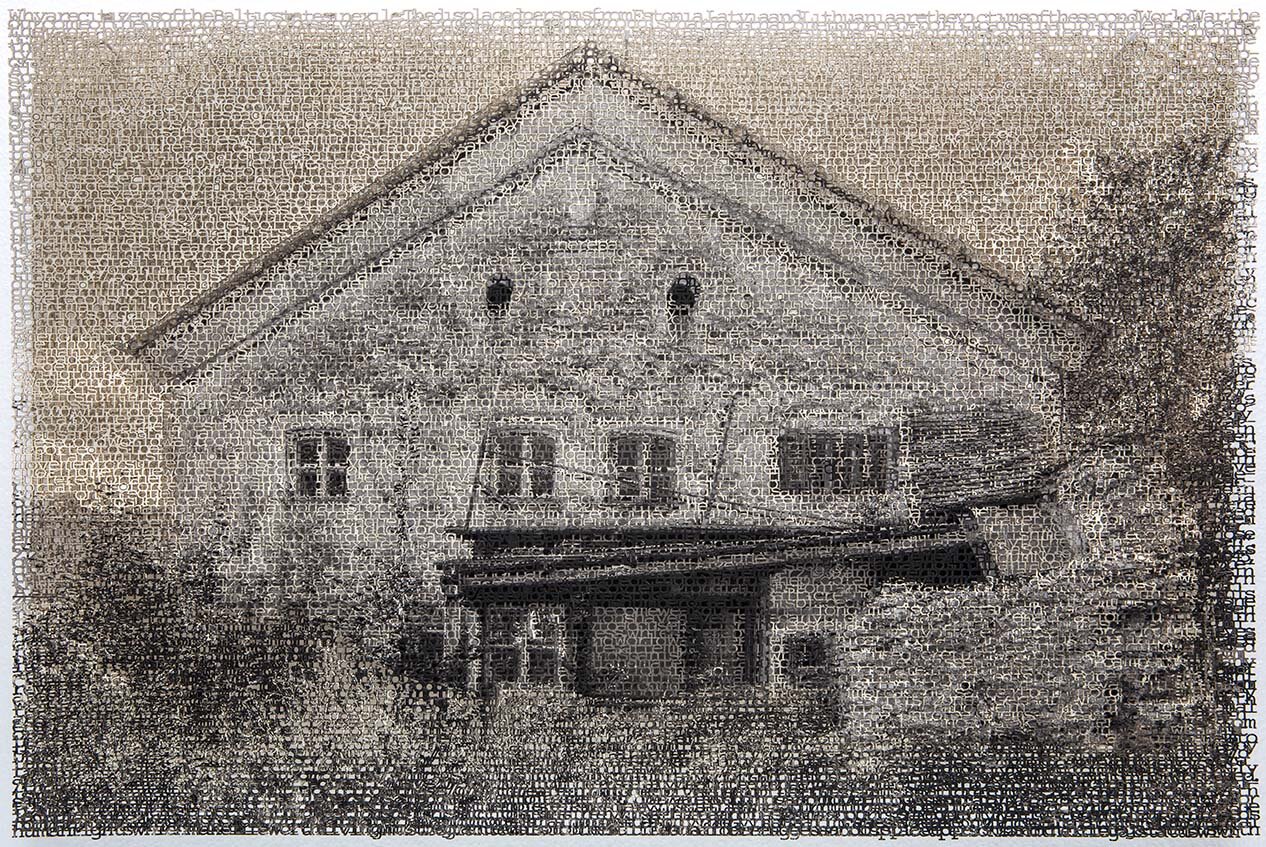

Displacement

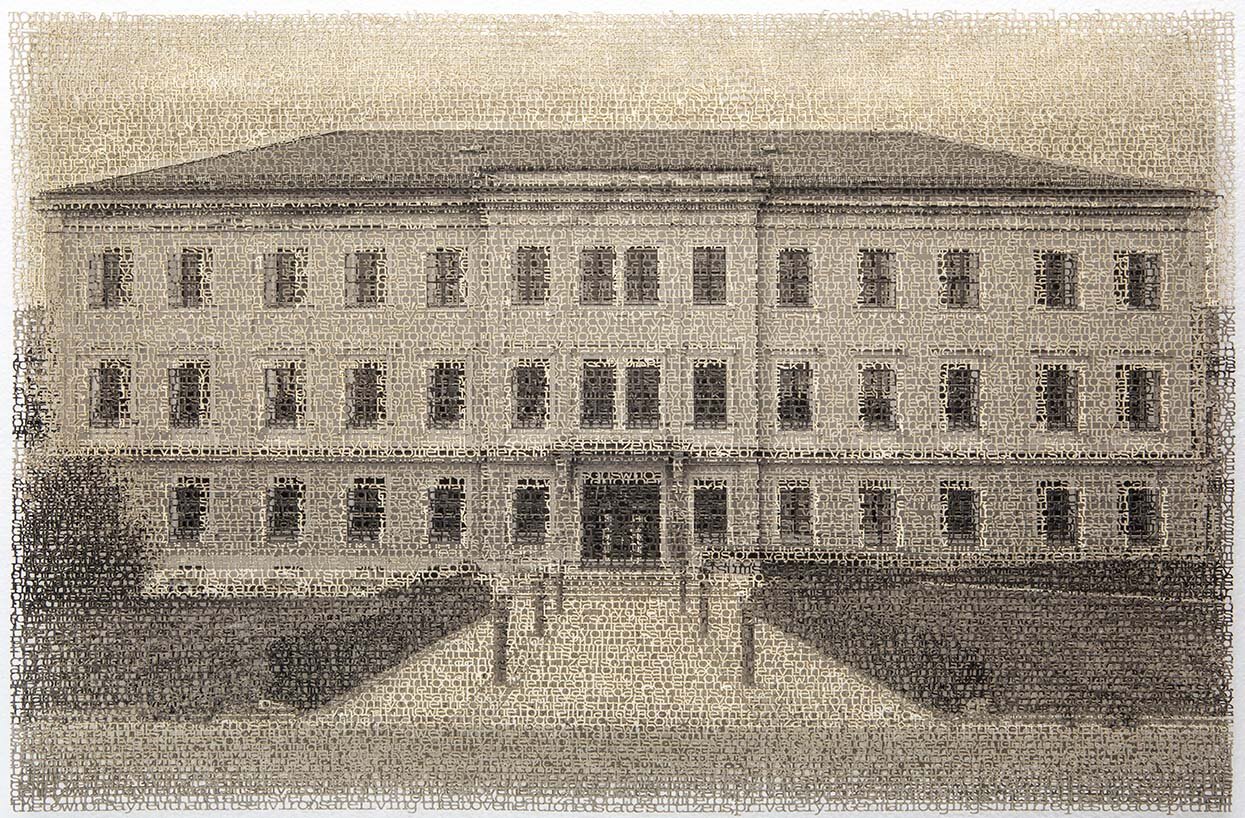

Ideas of home and dislocation have always been compelling to Krista Svalbonas as the child of immigrant parents who arrived in the United States as refugees. Born in Latvia and Lithuania, her parents spent eight years after the end of World War II in displaced-person camps in Germany before they were allowed to emigrate to the United States. In this series, Svalbonas set out to retrace and re-imagine that history.

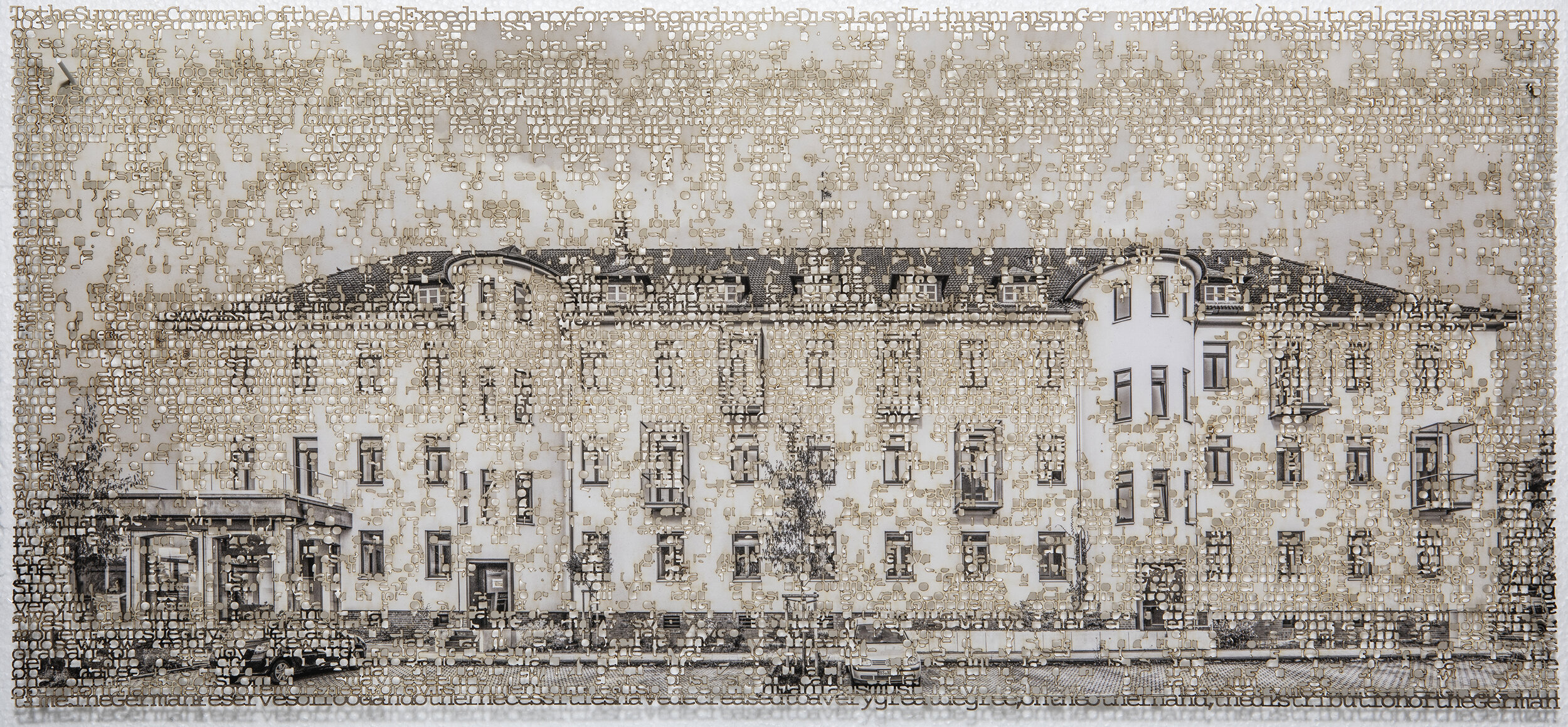

Svalbonas’ family’s displacement is part of a long history of uprooted peoples for whom the idea of “home” is undermined by political agendas beyond their control. Her parents’ childhood homes were impersonal structures appropriated from other civilian and military uses to house thousands of postwar refugees. They had always described this housing as temporary; she never expected to see these buildings herself. But after intensive archival research, Svalbonas was able to locate, visit, and photograph many of the actual buildings on the sites of former DP camps in Germany.

Today, the buildings give no hint of the tumultuous lives of the postwar refugees, stuck in stateless limbo with no idea what the future held. To better understand and honor their struggles, Svalbonas turned to archived copies of the plea letters the Baltic refugees sent to the governments of the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Page after page, they beg for food, bedding, and medical supplies, and attempt to explain the dire fate that would await them if they were repatriated to the Soviet Union.

Svalbonas merges these painful accounts with the photographs through a process of burning, an echo of the traumas of war the refugees had endured. The words of the refugees now form the complete image. Eventually made entirely of lace-like text, the buildings grow fragile, inseparable from the precarious lives they housed. A composite of my her experience and the fading memories of her parents and their generation, each of these layered pieces becomes a puzzle that Svalbonas is struggling to complete before this near-forgotten history is lost forever.